Featured Sponsor

| Store | Link | Sample Product |

|---|---|---|

| UK Artful Impressions | Premiere Etsy Store |

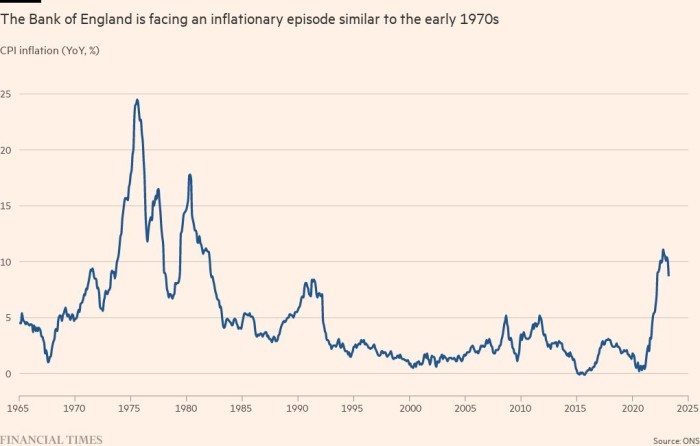

On the surface, UK inflation in 2023 is becoming similar to the problem of the 1970s, when there was talk of a “British disease” making the country the “sick man” of Europe.

Stubbornly high inflation eclipsing rates in other countries. Indexed contracts that amplify price pressures. Authorities struggling to control household costs. And wages follow higher prices.

Wednesday’s figures — they showed April inflation of 8.7%.far above the 8.4 percent expected by the Bank of England, he stressed that Britain appears to have a particular problem.

The country is feeling both the impact of robust government spending at a time when labor markets are tight – a problem also for the US – and the residual effects of a huge increase in wholesale gas prices in Europe lo last year.

But with Inflation in the UK significantly higher than in almost all other Western European countries and the BoE has repeatedly made too optimistic forecasts, excuses are running out.

Stephen King, HSBC Senior Economic Advisor and author of We need to talk about inflation, has been sour after the release of Wednesday’s figures by the Office for National Statistics.

“It doesn’t look good, does it?” said the king. “Depressed growth, not helped by Brexit. Real wage resistance. Core inflation is the highest in decades. The BoE admits that it has used a model that hasn’t worked well lately. Official rates are still very low compared to 6.8 per cent of core inflation. . . Oh dear.”

Inflation in the UK is now much higher than the eurozone average of 7%. The only other two Western European countries with rates above 8% are Italy – where inflation is the same as the UK – and Austria. Food prices are still rising at a rate of 19.1% in April.

Adding to the feeling that the UK is in danger, the London School of Economics released new research on Wednesday showing Brexit trade barriers contributed 8 percentage points to the 25% rise in food prices between 2019 and March 2023.

For three consecutive months, the BoE has also been caught off guard, failing to understand the short-term dynamics of prices. In February, the central bank expected inflation to fall to 9.2% by March, but it remained at 10.1%.

When the BoE revised its forecasts this month, it inserted new margins of error to improve accuracy. Privately, officials said the central bank had gone to great lengths to ensure forecasts weren’t too optimistic again.

BoE Governor Andrew Bailey admitted on Tuesday that the bank had “very great lessons to learn” on inflation control and its forecasting.

He said the failure to understand the immediate pressures on food prices was in part the result of adverse weather conditions in Morocco that the BoE could not have predicted, affecting supply chains of perishable items such as cucumbers and tomatoes.

But Bailey also acknowledged that the BoE hadn’t realized that food producers had entered into long-term wholesale contracts on global food commodity prices, which were close to last year’s peak.

It is clear that even the governor did not see last month’s 1.2% rise in prices in the UK. Nor did he expect the price hikes to be so large, driven by the rising cost of second-hand cars and sharp increases in the tariffs of cell phones, as well as books, sports and gardening equipment and pet products.

The rise in mobile phone rates was partly due to indexed contracts, a feature of life in the 1970s and still a reason inflation persists today.

Even before the latest forecast errors, BoE officials had been under pressure on Tuesday to explain themselves to MPs on the House of Commons Treasury Committee.

Although Bailey said the bank had already used his judgment to boost its forecasts, he was criticized by Harriett Baldwin, chair of the committee, for using a model based solely on data that reflected 30 years of relative price stability.

Huw Pill, the BoE’s chief economist, said the central bank was poring over historical data to figure out how to control inflation. “We think about it [whether] we should use models or revisit structures that were applied to data from the 70s and 80s,” he said.

“But more importantly, while there may be something to be learned from this, there are also reasons to think the experience isn’t immediately relevant,” Pill added.

Inflation remained persistent over those decades, Pill said, because companies and employees began to expect inflation to stay high, setting prices and demanding wage increases accordingly.

Even though Bailey has accepted that a wage-price spiral is amplifying inflation, its chief economist said the current situation is different from what it was in the 1970s.

“The structure of the labor market is very different. . . and in particular the regime in which monetary policy is conducted is very different,” Pill said.

The BoE has stressed that most of the inflation has come from sharp increases in the price of gas and food, which the UK imports and over which the central bank has no control.

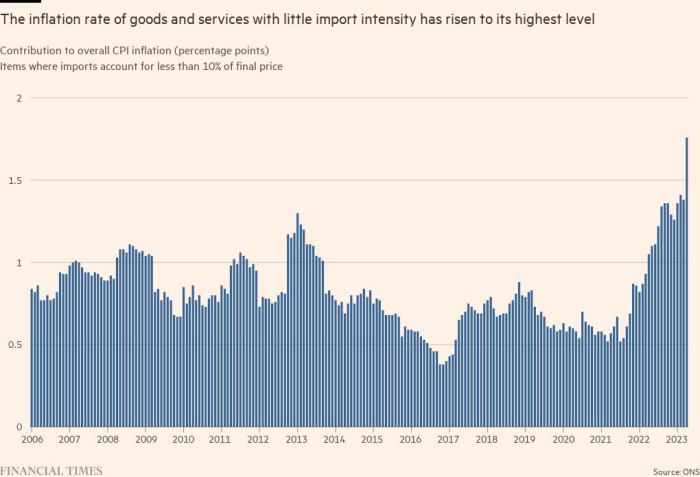

As economists pointed out Wednesday, the problem with the BoE blaming inflation on imported food and energy prices is that it is becoming increasingly inconsistent with the data.

Core inflation jumped from 6.2% in March to 6.8% in April, when economists’ average expectations expected it to remain constant.

Official data also showed that goods and services that contained few imported elements were increasingly adding to the overall inflation rate.

The ONS said that items that had an import intensity of less than 10%, such as house rentals, contributed 1.76 percentage points to the 8.7% inflation rate in April. That’s up from 1.38 percentage points in March and the highest level since the series was first published in 2006.

Allan Monks, UK economist at JPMorgan, said this was alarming and would prompt the BoE to raise interest rates further.

“[The data] it cannot be described as a one-off or simply an indirect byproduct of food and energy price hikes, as the BoE and the dovish have tended to suggest until very recently,” Monks said.

The echo of the past spooked financial markets on Wednesday, driving expectations about future interest rates sharply higher. The financial markets expect rates to rise to 5.3% by the end of the year.

That could outweigh the problem, according to Sandra Horsfield, a UK economist at Investec, who expects another quarter-point increase to 4.75% in June.

In a period of 1970s-style stagflation, with little growth and high inflation, he said: “Little can be ruled out, but it is arguable that much harder braking is needed.”

—————————————————-

Source link

We’re happy to share our sponsored content because that’s how we monetize our site!

| Article | Link |

|---|---|

| UK Artful Impressions | Premiere Etsy Store |

| Sponsored Content | View |

| ASUS Vivobook Review | View |

| Ted Lasso’s MacBook Guide | View |

| Alpilean Energy Boost | View |

| Japanese Weight Loss | View |

| MacBook Air i3 vs i5 | View |

| Liberty Shield | View |