Introduction

Maternal morbidity and mortality rates remain unacceptably high in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).1 According to the most recent Pakistan Maternal Mortality Survey (PMMS), the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) in Pakistan was 186 deaths per 100,000 live births, with Sindh having the second highest MMR after Baluchistan.2 Although Pakistan’s MMR has decreased over the years, efforts must be doubled if we are to meet the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) targets by 2030.3

Antenatal care (ANC) plays a critical role in preventing maternal morbidity and mortality.4 It offers a range of services that include administering preventive measures such as immunizations and educating pregnant women on healthy behaviors during pregnancy and identifying and managing potential complications. Despite its benefits, the perception and experiences of pregnant women significantly influence the utilization of ANC services.4 Low satisfaction rates with the quality of care offered at the ANC facilities can discourage women from attending ANC visits, leading to missed opportunities for preventive measures and timely management of high risk pregnancies.5 Negative perceptions and experiences are often attributed to poor interactions with health professionals, inadequate provision of health information, delayed care, limited involvement in decision-making, and suboptimal conditions of the health facilities, including lack of privacy and cleanliness.6 These factors have been associated with negative ANC experiences, leading to ANC dropouts during pregnancy.7,8

To tackle the high burden of poor maternal outcomes in Pakistan along with the scarcity of a trained healthcare force,9 the government has implemented various programs, including the Lady Health Workers and Community Midwives (CMW) programs, to address the shortage of skilled health workers.10 These models are widely recognized as a progressive, sustainable, and cost-effective approach to improving maternal and newborn outcomes. However, these seem to be more focused on clinical knowledge rather than technical and soft skills.11,12 This is also evident as a gap in the literature regarding pregnant women’s experiences with midwifery-led ANC services in Pakistan, which would be an important indicator of uptake of these services.

One of the frameworks that can be used to understand this experience is the Respectful Maternity Care (RMC) charter. This charter supports the rights of pregnant women and promotes dignified and respectful care during pregnancy.13 Implementation of such practices could improve the effectiveness of midwifery-led services in reducing maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity in underserved areas. Thus, this study aimed to understand pregnant women’s experience with midwifery-led antenatal care services using the Respectful Maternity Care charter in primary health centers in Karachi, Pakistan.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

This cross-sectional study was conducted from January to December 2021 at two primary health clinics (PHCs) located in peri-urban communities of Karachi, Pakistan. These communities (ie, Ibrahim Hyderi and Rehri Goth) are homogenous low-income communities situated in Bin Qasim town of the coastal region of Karachi. These sites are part of the Pregnancy Risk Stratification: Innovation and Measurement Alliance (PRiSMA) study, which is coordinated by George Washington University, whose primary aim is to create a harmonized data set to improve global understanding of key risk factors, vulnerabilities, and morbidity and mortality outcomes during the pregnancy and postpartum period. Each study site has four midwives with a diploma in midwifery who provide ANC services to 20–25 pregnant women per day.

Population & Eligibility Criteria

Eligibility criteria for PRiSMA study included pregnant women living within the study catchment area, at least 15 years old, with an intrauterine pregnancy verified via ultrasound at less than 20 weeks gestation and provided informed consent. All women enrolled in the PRiSMA study and in their third trimester during the defined study period were considered eligible to participate.

Sample Size Determination and Sampling Procedure

There was no predefined sample size for the study. Instead, data was collected from all third-trimester women who visited PHC between January and December 2021 and agreed to participate in the study.

Data Collection, Procedures, and Data Quality Control

As part of the secondary objective of PRiSMA, the women’s experience regarding healthcare accessibility, antenatal care, ANC experience, and overall satisfaction with the facility was recorded on a Likert scale using a pre-designed questionnaire on an android tablet. The questionnaire was developed based on the Demographic Health Survey (DHS) Program Service Provision Assessment (SPA) CEI tools, the Kenyan person-centered maternity care scale, and the 2015 Nepal Service Provision Survey (SPA) Client Exit Interview.14–16 After obtaining written informed consent in the local language (Urdu) for the interview, an independent study staff member with at least 12 years of education conducted in-person interviews with the study participants.

To ensure the quality of data collected, the data collectors underwent a rigorous two-day training on the questionnaire, data collection procedures, and ethical considerations. Additionally, study field supervisors conducted spot checks on a random sample of 10% completed questionnaires weekly to verify the accuracy of the collected data.

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments and was approved by the institutional Ethics Review Committee at The Aga Khan University (2021–5920-15,518).

Statistical Analysis Plan

For analysis, the questions were mapped onto the universal Respectful Maternity Care (RMC) charter (Table 1), which outlines women’s maternity care rights.13 Articles 1 and 7–10 were not covered in the study questionnaire, and hence, only articles 2–6 were included in the analysis. Additionally, questions regarding client’s general satisfaction with the PHC facilities were included as a separate theme, namely “General Facility Satisfaction”.

|

Table 1 Articles of the Respectful Maternity Care (RMC) Model with Their Definitions Matched with Questions from the CEI questionnaire15 |

All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA version 14.2. The descriptive statistics for the study variables were reported using mean and standard deviation for continuous variables such as age, and frequency and percentages for categorical variables such as women’s experiences. The Likert scale “yes all the time” and “yes most of the time” were combined to create a single category labelled as “yes”, the other categories were retained as “no” and “do not know”. Initially, all outcome variables on RMC were assessed at a univariate level against age, woman’s education, woman’s occupation, and parity. Variables that had a p-value of less than 0.25 at the univariate level (refer to Table S1) were included in the subsequent multivariable logistic regression analysis. The stepwise backward elimination method was used to build final model. A p-value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 970 women were approached, out of which 904 pregnant women (93%) consented to participate in the study. The mean age of the participants was 27.3 ± 6.2 years, of which 75% (n=673) were multiparous. The baseline characteristics of the study participants are described in Table 2. The study’s results are presented in accordance with the RMC’s themes described in Table 1, along with findings of the client’s general satisfaction with the PHC facilities.

|

Table 2 Baseline Characteristics of Women Enrolled in the Study |

General Facility Satisfaction

In this section, we enquired regarding satisfaction with the ambience and waiting hours at the facility. The most common reasons identified for choosing the PHC facility were encouragement by the field staff (37%, n= 336), familiarity with the midwives (35%, n=320), and the availability of free services (14%, n= 128). Furthermore, the results showed that 97% (n=884) of the participants were satisfied with the operational hours of the facility. Also, 88% (n=797) of the women found the facility to be clean. Half of the respondents (50%, n=456) reported that they had received services at the facility within an hour of waiting. The odds of satisfaction among employed women was three times higher compared to unemployed women (AOR=2.99; 95% CI: 2.08–4.30) (refer to Table 3).

|

Table 3 Multivariate Analysis Showing Factors Associated with Maternal Satisfaction with Antenatal Care in Public Health Centers |

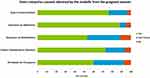

Article 2 – Right to Information

Pregnant women were asked regarding information provided related to current examination. Sixty percent (n=542) of women reported that midwives took permission before performing any exams, and Fifty three percent (n=481) reported understanding the need for those examinations when explained by the midwife (refer to Figure 1). Furthermore, pregnant women also reported high satisfaction with sessions related to a healthy pregnancy (75%, n=677). However, only 43% of the women expressed satisfaction with nutritional counseling (n=395) and 13% with counseling on birth preparedness (n=119).

|

Figure 1 Items related to consent obtained by the midwife from the pregnant woman. |

Study participants who were literate were more likely to report satisfaction with understanding the need for examinations and nutritional counselling than women with no formal education (OR = 1.69; 95% CI: 1.29–2.23) and (OR = 1.59; 95% CI: 1.21–2.09), respectively). Employed women reported lower satisfaction with nutritional counseling (OR=0.56; 95% CI: 0.43–0.75) and with the process of obtaining permission before conducting examinations and procedures (OR=0.17; 95% CI: 0.11–0.28) compared to unemployed women. Additionally, women with a high parity were more likely to recall healthy pregnancy counselling than women who were pregnant for the first time (OR = 1.46; 95% CI: 1.01–2.11).

Article 3 – Privacy and Confidentiality

The majority of pregnant women (99%, n=892) reported that their privacy was ensured by providing a cover or screen during the examination.

Article 4 – Dignity and Respect

Pregnant women reported high satisfaction with respectfulness (99%, n=899), friendliness (99%, n=898), and addressing women by their name (100%, n=900) by the midwives at the health facility. Even though majority of the women felt respected when asked if they would take any action against the care provider in case they felt wronged or disrespected, 41% (n=374) reported that would prefer not to take any action. Employed women were less satisfied as compared to unemployed women regarding respect provided (OR = 0.17, 95% CI: 0.11–0.28) and increasing age was associated with a higher likelihood of feeling respected (OR = 1.04; 95% CI: 1.01–1.07) than their counterparts.

Article 5 – Equitable Care

Majority of pregnant women felt that staff spoke to them in a language they understood and did not feel any discrimination based on ethnicity or educational status (99%, n=897 and 97%, n=880), respectively.

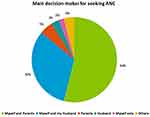

Article 6 – Right to Healthcare

The distribution regarding decision-making to seek ANC at the health facility has been shown in Figure 2. Approximately 34% (n=309) reported that they decided to seek care either with their husbands or independently. To assess whether pregnant women had access to their right to healthcare and the highest attainable level of health, they were evaluated based on their ability to recall counseling regarding complications during pregnancy, labor and delivery, and newborn counseling provided by the midwife. Fifty-nine percent of women (n=479) were able to recall at least four danger signs out of eight. Additionally, fifty-nine percent of women (n=536) were able to recall all three labor signs, whereas only 39% (n=351) women were able to recall any neonatal danger signs. In the event of an emergency, 50% of women (n=454) reported they would call a midwife, while the remaining (48%, n=430) said they would attempt to visit the health center or referral hospital.

|

Figure 2 Main decision-makers for seeking ANC. |

Discussion

This study reported pregnant women’s satisfaction with midwifery-led services at a PHC in a peri-urban community in Pakistan. Women reported high satisfaction with respect to general facility conditions, provider attitude and service, and availability of timely care at the PHC. However, findings suggested that pregnant women’s right to information, informed consent, and preferences needed significant improvement with respect to the provider-patient encounter.

Midwives are potential solutions to skilled-care provider shortages and have been shown to significantly prevent and lower morbidity and mortality in mothers and newborns.11 This study aimed to understand the experience of pregnant women on RMC attributes in our health facility. The RMC Charter is a global advocacy tool aimed at strengthening the rights of mothers and their newborns in relation to the maternity care offered at health facilities.13 It served as a framework for mapping the study tool to understand the experience of pregnant women with RMC attributes in our health facility. Most studies have assessed the impact of the RMC charter as a model for promoting good practices during intrapartum and postpartum care.13,17 In contrast, the current study focused on assessing the gaps during the ANC period.

The facility’s physical infrastructure, regarding waiting areas and overall cleanliness, is known to impact women’s ANC experience significantly.18 Even though there were some concerns with waiting time of > 30 minutes, which have shown to have a negative relationship with women’s satisfaction and poor compliance to ANC visits,19 the current study reported high satisfaction with the facility’s general services and cleanliness.

In more traditional cultures such as ours, mothers-in-law or elders have the authority to make pregnancy-related decisions, particularly for young women.20,21 The current study saw a similar trend where women’s ability to seek ANC services and make independent decisions was much lower (2.5%) and was instead influenced by their increasing age and parity. This poor decision making also extends during the patient provider encounter where patients often feel unable to provide fully informed consent for procedures and examinations due to the lack of adequate debriefing by health providers and insufficient opportunities for involvement in decision-making.22,23 The lack of this decision-making ability also violates the patient’s rights specified by the World Health Organization.24 Eight percent of women in the current study reported that midwives performed exams or procedures without obtaining consent. However, 99% of the women reported that their privacy and confidentiality were maintained throughout the ANC encounters. Notably, the lack of literature on patients’ experiences during antenatal visits in LMIC further distinguishes this study.25

The current study reported that, while most women had better recall of pregnancy danger signs and labor signs, their retention of information regarding healthy pregnancy, nutritional counseling, and newborn care was comparatively poor. This is consistent with findings by Assaf et al, who suggested that the recall patterns could be due to lack of attention by pregnant women during information provision or midwives imparting excessive information in a short period, thus overwhelming the women.26 Poor literacy status of pregnant women (as seen in the current study) may be a contributing factor to the knowledge gaps identified.27 At the provider’s end, midwives in such settings may need more time to perform routine check-ups as well as offer counseling to every woman at each visit.28 Further, in the study context, postnatal care is mainly provided at home through community health workers. As a result, the midwives may not prioritize counselling on this aspect, as it falls outside of their direct responsibility. Regardless, the charter requires providers to switch from a disease-focus to a patient-centered approach and improve their interpersonal skills to adhere to the RMC standards.13 Findings from one study highlight the potential for tailored interventions such as the use of visual aids, culturally appropriate materials in local languages, and group education sessions led by community-based volunteers along with efficient governmental policies in improving health knowledge among women with limited literacy skills.29

Due to the limited literature available in this area, the current study adds to the evidence of adherence to the RMC charter in a midwifery-led facility in a low-resource setting. These findings may have implications beyond Pakistan, including increased awareness and advocacy for midwifery practice in countries with similar maternal and child health challenges. The study is limited in terms of its sample, as it was conducted in a single region of Pakistan, which may limit its generalizability to the wider population. Even though we tried to maintain privacy, there may be potential respondent bias. Further, a solely quantitative approach may not comprehensively capture the women’s perception of care. Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable insights and highlights areas for further research and improvement.

Conclusion

The study findings provide a nuanced perspective on the significance of understanding the pregnant women’s experience in midwifery-led care in an LMIC. This study has highlighted opportunities to improve midwives’ compliance with RMC attributes, thereby improving the patient-provider encounter. RMC training, in addition to technical training, would assist midwives in improving their knowledge of routine maternity care procedures and adopting a patient-centered approach, potentially leading to significant improvements in practice and maternal and newborn health outcomes.

Abbreviations

ANC, Antenatal care; PHC, Primary Health Centre; RMC, Respectful Maternity Care; LMICs, Lower-Middle-Income-Countries; PMMS, Pakistan Maternal Mortality Survey; CMW, Community Midwife; MMR, Maternal Mortality Ratio; SDG, Sustainable Development Goals; CEI, Client Exit Interview; DHS, Demographic Health Survey; SPA, Service Provision Assessment; BMGF, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; PRiSMA, Pregnancy Risk Stratification Innovation and Measurement Alliance.

Data Sharing Statement

Researchers may request access to anonymized participant-level data from the corresponding author.

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent

The Aga Khan University Ethics Review Committee approved the study (2021-5920-15518). Consent was obtained by the study participants prior to study commencement.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the participants who voluntarily took part in this study and the data collectors for their help in data collection.

Funding

The PRiSMA study was funded by the Bill &Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) (INV-005776). The funders had no involvement in any stages, from study design to manuscript submission for publication.

Disclosure

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1. Bauserman M, Thorsten VR, Nolen TL, et al. Maternal mortality in six low and lower-middle income countries from 2010 to 2018: risk factors and trends. Reprod Health. 2020;17(Suppl 3):173. doi:10.1186/s12978-020-00990-z

2. National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS) [Pakistan] and ICF. 2019 Pakistan Maternal Mortality Survey Summary Report. Islamabad P, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: NIPS and ICF; 2020.

3. Hafeez AZN, Ahmad I, Shahzad K. Improving Maternal, Newborn and Child Health Outcomes in a Decade, Pakistan Report 2020. Available from: https://www.countdown2030.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Pakistan-CD-report-2020.pdf.

4. Ali SA, Dero AA, Ali SA, Ali GB. Factors affecting the utilization of antenatal care among pregnant women: a literature review. J Preg Neonatal Med. 2018;2(2):e545.

5. Khatri RB, Mengistu TS, Assefa Y. Input, process, and output factors contributing to quality of antenatal care services: a scoping review of evidence. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22(1):1–5. doi:10.1186/s12884-022-05331-5

6. Jallow IK, Chou YJ, Liu TL, Huang N. Women’s perception of antenatal care services in public and private clinics in the Gambia. Int J Qual Health Care. 2012;24(6):595–600. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzs033

7. Nisar YB, Aurangzeb B, Dibley MJ, Alam A. Qualitative exploration of facilitating factors and barriers to use of antenatal care services by pregnant women in urban and rural settings in Pakistan. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):42. doi:10.1186/s12884-016-0829-8

8. Onyeajam DJ, Xirasagar S, Khan MM, Hardin JW, Odutolu O. Antenatal care satisfaction in a developing country: a cross-sectional study from Nigeria. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):368. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5285-0

9. World Health Organization (WHO). The Global Health Observatory. Number of Licensed Qualified Obstetricians Actively Working. World Health Organization; 2012.

10. Government of Pakistan. PC-1 National Maternal, Newborn and Child Health Programme (MNCH). Islamabad: Federal Ministry of Health; 2006.

11. Nove A, Friberg IK, de Bernis L, et al. Potential impact of midwives in preventing and reducing maternal and neonatal mortality and stillbirths: a Lives Saved Tool modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9(1):e24–e32. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(20

12. Siddiqui D, Ali TSJM. The importance of community midwives in Pakistan: looking at existing evidence and their need during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2022;48(1):47–53. doi:10.1111/jog.15035

13. White Ribbon Alliance. Respectful Maternity Care Charter; 2022 Available from: https://whiteribbonalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/WRA_RMC_Charter_FINAL.pdf.

14. The DHS program. Service provision assessment survey 2012. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-spaq3-spa-questionnaires-and-manuals.cfm.

15. Afulani PA, Diamond-Smith N, Golub G, Sudhinaraset M. Development of a tool to measure person-centered maternity care in developing settings: validation in a rural and urban Kenyan population. Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):118. doi:10.1186/s12978-017-0381-7

16. Nepal Ministry of Health, New ERA, NHSSP, ICF. Nepal Health Facility Survey 2015. Kathmandu, Nepal: Ministry of Health, Nepal; 2017. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SPA24/SPA24.pdf.

17. Dzomeku VM, Boamah Mensah AB, Nakua EK, Agbadi P, Lori JR, Donkor P. Midwives’ experiences of implementing respectful maternity care knowledge in daily maternity care practices after participating in a four-day RMC training. BMC Nurs. 2021;20(1):39. doi:10.1186/s12912-021-00559-6

18. Boller C, Wyss K, Mtasiwa D, Tanner M. Quality and comparison of antenatal care in public and private providers in the United Republic of Tanzania. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81(2):116–122.

19. Chorongo D, Okinda FM, Kariuki EJ, et al. Factors influencing the utilization of focused antenatal care services in Malindi and Magarini sub-counties of Kilifi county, Kenya. Pan Afr Med J. 2016;25(Suppl 2):14. doi:10.11604/pamj.supp.2016.25.2.10520

20. Tarar MA. Knowledge and Attitude; Pregnancy and Antenatal Care among Young Agrarian & Non-Agrarian Females in Faisalabad District, Pakistan. Pak J Agric Sci. 2019;56(1):261–273. doi:10.21162/pakjas/19.7730

21. Ghani U, Crowther S, Kamal Y, Wahab M. The significance of interfamilial relationships on birth preparedness and complication readiness in Pakistan. Women Birth. 2019;32(1):e49–e56. doi:10.1016/j.wombi.2018.03.005

22. Montesinos-Segura R, Urrunaga-Pastor D, Mendoza-Chuctaya G, et al. Disrespect and abuse during childbirth in fourteen hospitals in nine cities of Peru. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;140(2):184–190. doi:10.1002/ijgo.12353

23. Nicholls J, David AL, Iskaros J, Lanceley A. Consent in pregnancy: a qualitative study of the views and experiences of women and their healthcare professionals. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;238:132–137. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2019.05.008

24. The prevention and elimination of disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth: world Health Organization; 2014. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/134588/WHO_RHR_14.23_eng.pdf.

25. Mihret H, Atnafu A, Gebremedhin T, Dellie EJ. Reducing disrespect and abuse of women during antenatal care and delivery services at injibara general hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: a pre–post interventional study. International Journal of Women’s Health. 2020;12:835. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S273468

26. Nicholls JA, David AL, Iskaros J, Siassakos D, Lanceley AJBP. Consent in pregnancy-an observational study of ante-natal care in the context of Montgomery: all about risk? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):1–9.

27. Assaf S. Counseling and Knowledge of Danger Signs of Pregnancy Complications in Haiti, Malawi, and Senegal. Matern Child Health J. 2018;22(11):1659–1667. doi:10.1007/s10995-018-2563-5

28. Gilder ME, Moo P, Hashmi A, et al. “I can’t read and don’t understand”: health literacy and health messaging about folic acid for neural tube defect prevention in a migrant population on the Myanmar-Thailand border. PLoS One. 2019;14(6):e0218138. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0218138

29. Meherali S, Punjani NS, Mevawala A. Health Literacy Interventions to Improve Health Outcomes in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Health Lit Res Pract. 2020;4(4):e251–e266. doi:10.3928/24748307-20201118-01

—————————————————-

Source link